The Iron Flood

The Battleship Potemkin of literature

“Did there really live such a Kovtyukh? Could there really be such heroes? I can’t believe it, although I want to believe it!”

★★★★ These are the words of a French Renault worker to the Communist newspaper L’humanité after reading Alexander Serafimovich’s novel. I confess that when I first read it, I thought it was an amalgam of numerous experiences throughout the Red Army throughout the Russian Civil War (really an undeclared external war waged by a dozen capitalist countries and their proxies). I had no idea this was the dramatic account of a single army—the tribulations of the Taman Army from August–September 1918.

The novel opens with a raucous mob in a Cossack village on the steppe: diapers hang on rifles, children cry, cows munch hay beside artillery horses, women cook kettles full of millet and suet over fires fed with dried dung. Even the kites soaring above do not know what to make of the scene:

Was it a country fair? Where, then, were the tents and traders with their heaped merchandise?

Was it a settlers’ camp? But why the guns and limberchests, the army carts and the stacked rifles?

Was it an army?

But why were there babies crying all over the place, young mothers suckling them?

This ragged mass of 30,000 men and 25,000 refugees—camp women, children, parents and grandparents—crossed 500 kilometres of Circassian steppe, forest, and mountain to join the main body of the Red Army in the North Caucasus.

One sees the word “army”, thinks professional soldiers in uniform, in organised units, in columns, all armed and armoured and provisioned. This is Serafimovich’s first note on the Taman Army:

- Internet Archive (PDF) Free! (EN)

- Maksim Moshkow Internet Library (HTML) Free! (RU)

As the language is dated, we highly recommend reading along with this chapter guide by SovLit.net.

“Desperate fighters. They retreated from the Taman Peninsula. To each four to five mess tins (that is, rations cut by 4-5 rolls). Badly dressed. Sometimes only trousers and ragged shoes, and the torso is naked. He girdled round his naked body a bandolier, thrust in a revolver. War—this is the craft of war.”

The book is deservedly hailed as an “epic” and a “monument” of Russian literature, but it is barely over 200 pages long. But you will take time reading it, for it is difficult to read… Not because of the dated language, though that may certainly be a factor, but because Serafimovich paints the daily life of the Taman Army with such vividness. You are with them when they sit down to play the balalaika and flirt with their sweethearts next to the campfires, when the burly, foul-mouthed and near-mutinous Black Sea Fleet sailors, armed with bombs, come to harass the peasant soldiers. And you are there when they are forced to leave the injured veterans at the port city of Novorossiysk, to be slaughtered by the Cossacks on their tail, and you are there when the living sit again around campfires, in silence, haunted by the raped and dead after a witness tells them all that happened.

You are there when a young mother, one you recognise—was it only a few nights ago she was laughing with the boy, with bubbling mouth? when her and the father’s laughing adorations for him pierced the darkness?—loses her child to hunger, and crazed, attempts to nurse the corpse at her breast. You are there when the father—you definitely recognise him—arrives at the refugee caravan from the front column after being sent for, when his young wife presents a cold reeking bundle to him.

“Cossacks, a hundred of them, violated her by turns. She died under them. She was a nurse in our hospital. Short cropped hair like a boy’s and always barefoot. A factory girl. So active and clever. Wouldn’t forsake the wounded.”

Click on the image to view it in full.

You are there when the horses collapse and the dogs run away, and when the slender-waisted Circassians of the army, in their dashing long coats, elegant fur hats, leather girdles and sabres, surge forward across the bridge on their horses to clear the way for their comrades behind them, mowed down by Georgian machine-guns.

A salvaged gramophone plays, and the snaking army laughs with one voice. And in between the song and talk, you think of the dead. You wonder how much longer this march will take. How many more children will have to be abandoned, still alive, in the dust. You see the officer who had salvaged from a clothing store something that he reasoned was a “new type of trousers”—the other men informed him he was wearing women’s lacy ruffle shorts. You see, though you aren’t surprised, with how sheer the material is, that that too is falling apart.

This is a portrait of a people, much in the same way Sergei Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin, released just a year later in 1925, is a portrait of the Black Sea Fleet and the people of Odessa.

From Serafimovich’s notebook:

«Отчаянные рубаки. С Таманского полуострова отступали. У каждого четыре-пять котелков (то есть, срубили 4-5 голов). Плохо одеты. Иногда одни штаны да рваные башмаки, а торс голый. Он подпоясывался, через голое тело надевал патронташ, засовывал револьвер. Война—ремесло.»

There are recurring characters: Ukrainian Commander Epifan I. Kovtyukh is one of them, and in this peasant-born officer is embodied the revolutionary spirit of the best of the Bolsheviks. He is the only one with the nerve to lead the army out of the encirclement—the other generals were eager to take over command until he resigned, and the soldiers—a second time—nominated him commander. And they all affectionately called him “Batko”, a Ukrainian term of respect meaning “Father”. It is a title that he earned through courage, wit, dogged persistence, and integrity.

There is no dressing up of the war in Serafimovich’s text. The brutalities, executions, deprivations, and griefs are on full display here—as are the fleeting joys.

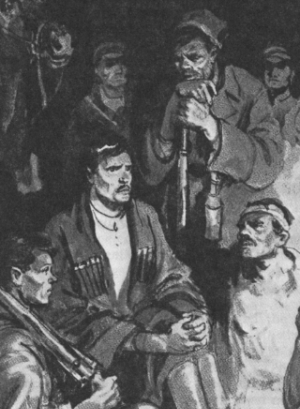

Something else could be said of Anatoly Kokorin’s illustrations. They are lively, and his pen sketches are of lightning clarity—but some of his depictions of the Taman Army later in the book are bafflingly romantic when compared to the horrific, blackening starvation and malnutrition described by the author. Even the camp dogs have run off, the dearth of food being so great.

Some background:

Though the Reds were superior in both arms and men, German imperial forces had driven the Red Army out of the Kuban, leaving the Bolsheviks in the Taman Peninsula isolated. These were encircled and chased on all sides by Georgian Mensheviks, Cossacks, and the White Volunteer Army, with the Germans and Ukrainians patrolling the coast in warships. Kovtyukh organised the army into three columns: the first, vanguard column fought through and chased down the Georgian Mensheviks. The second middle column repulsed the attacks of White Cossacks. The third column, the rearguard, batted off the White Volunteer Army. Trailing them were the refugees, and also the sailors, whom Kovtyukh did not allow too close to the soldiers as they were anarchic and treasonous.

During the Civil War, Serafimovich was a correspondent for Pravda and head of the Literary Department of the People’s Commissariat for Education. He worked on the novel for more than two years, and intended it as the first part of a series of works based on the Russian Revolution. However, this was the only work that was completed. Serafimovich researched the memoirs of those living in the Kuban, studied essays, and interviewed Kovtyukh and other veterans of the Taman Army.

Kovtyukh expressed great interest in a screenplay of the march of the Taman Army, and in playing himself in the film adaptation, recalled Colonel-General Leonid M. Sandalov in his memoir Surviving. A popular film adaptation was made—in 1967, and a low-resolution version has been made publicly available by the rights-owner MosFilm.

Beloved Batko was, like many of the Old Bolsheviks who led in the revolution, massacred in Stalin’s purges. Kovtyukh was arrested on August 10, 1937 on suspicion of participating in a fascist military conspiracy to overthrow the Soviet government and branded as “the leader of peasant fascism”. His wife Agafya Andreevna spent eight years in prison, and his son Valentin, five. He was tortured for 350 days in Lefortovo prison, called to “interrogations” no fewer than 69 times. On July 26, 1938, Stalin placed him on the execution list. He was executed three days later.

In prison Kovtyukh wrote this heart-breaking letter to Mikhail Kalinin, the Chairman of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee:

“I appeal to you as a member of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and ask you to consider my disastrous, threatening situation at the Presidium. Why I die and why such a cruel reprisal against me—I do not know. Several unreasonable charges were brought against me, the facts were not reported, because they do not and cannot exist… As I fought for the Soviet regime, you are well aware that the whole people know about them. My health is deteriorating every hour. Please convey my sincere greetings to Comrades Stalin and Voroshilov. I’m ending with tears and I hope that you will save my life.”

Batko, though scrubbed from official records and the history books, persisted in Serafimovich’s The Iron Flood, studied as a work of classical literature throughout the USSR. He was rehabilitated on February 23, 1956.

Alexander Serafimovich survived till January 19, 1949. He stayed on cordial terms with Stalin, personally sending Stalin a letter in April, 1943 informing him that he was donating the monetary portion of his Stalin Prize (awarded for literary excellence), 100,000 rubles, to the war effort during World War II.

The book is available for free in Russian on the Maksim Moshkow Internet Library and in English on the Internet Archive. As the language is dated, we highly recommend reading along with this chapter guide by SovLit.net.

Batko’s letter in prison:

«обращаюсь к Вам как член ВЦИК и прошу на Президиуме рассмотреть мое катастрофическое, угрожающее положение. За что погибаю и зачем такая жестокая расправа со мной—не знаю. Мне предъявили несколько необоснованных обвинений, фактов не сообщили, потому что их нет и не может быть… Как я дрался за Советскую власть, Вам хорошо известно, о них знает весь народ. Мое здоровье с каждым часом ухудшается. Прошу передать мой искренний привет т.т. Сталину и Ворошилову. Я со слезами заканчиваю и надеюсь, что вы спасете мою жизнь.»