Train to Busan

South Korea, covered in blood

★★★☆ The 2016 film Train to Busan is currently one the top-viewed films on Netflix in the US. A film about how contemporary society faces—and collapses after failing to rationally and humanely treat a deadly epidemic. I wonder why such a film could possibly be so popular at this very moment.

But it’s more than just the COVID-19 pandemic. There are plenty of films about zombie plagues—take Edgar Wright’s and Simon Pegg’s brilliantly funny Shaun of the Dead, for example, or either of the Dawn of the Dead films. Or the ongoing (and ongoingly stupid) The Walking Dead TV series. Hearing Anglophones don’t need to read the subtitles for those original English-language works.

Yeon Sang-ho’s Train to Busan has been likened to Snowpiercer with zombies, but I think it’s more accurate to compare this to Parasite. Both films, while offering the viewer a good bit of action and humor, treat both gently and incisively the fraying of broader social and more intimate personal bonds under the parasitism of modern capitalism.

The male lead, Seok-woo (Gong Yoo) is a professional bloodsucker—a hedge fund manager—“Don’t say that in front of his child!” His ten-year-old: “It’s OK. It’s what everyone’s thinking.”—who doesn’t hesitate to tell his subordinate to disregard the “lemmings” of the economy, the hapless masses who can’t keep up in his man-eat-man world.

Seok-woo is kind of a shitty dad and overall a shitty person, but the film makes it clear that to expect more from him under normal circumstances, in normal society, would be stupid. His daughter Su-an (Kim Su-an—[Tolly] They share the same given name, how cute!) rightfully calls her old man a neglectful liar, his estranged ex-wife doesn’t expect him to remember that his own daughter’s birthday is tomorrow (and he only half-remembers this), the rest of society expects nothing of him but an efficient leech and that’s what South Korea has turned him into.

The country was already a man-eat-man hell. A zombie plague just sped up the process a little, that’s all.

Food and its treatment plays a subtle but significant part in Train to Busan. Seok-woo takes his lunch, a bunch of fastfood crap, on his desk, and unceremoniously discards the packaging without a second thought. The old woman (Lee Joo-sil) who takes care of his daughter—I mistook her for “the help” but it turns out she’s Seok-woo’s mom—carefully and meticulously prepares individual anchovies for the girl’s favorite dish by hand. A pregnant woman gives the girl a gummy worm to cheer her up, and another old woman gives her a treat as thanks for offering up her seat. The start of the film has a rough-mouthed farmer complaining of the local biotech company killing off his livestock. Who’s eating who—or what? And how is that food shared, if at all?

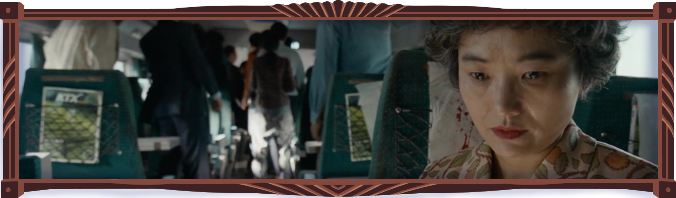

21st century South Korea may have modern trains, smartphones, and possibly an excess of Nintendo Wii-Us, but it’s built on blood. Two old women, survivors of General Chun Doo-hwan’s military junta in the 1980s, Jong-gil (Park Myung-shin) and In-gil (Ye Soo-jung), watch the violent “riots” on the news and the equally violent state-repression sent to quash them, and recall the Gwangju massacre and the “re-education camps” that drove political dissidents to death by harsh labor and torture. It’s 2016, and South Korea still grinds a good portion of its citizens into the dust of abject poverty, all the while cultivating the worst antisocial scum and elevating them to luxury and power.

The biotech company responsible for the plague covers up the outbreak at its facilities for as long as possible, while the insiders at the top sell off all their assets at breakneck speed before the cat is let out of the bag and the market crashes. South Korea’s government is equally reticent—OK look, they just don’t give a crap—to release any information about the outbreak to even those workers involved in key infrastructure, like transportation. The train’s passengers turn to social media, viral videos, and personal contacts to keep themselves informed. The word “zombies” is never uttered in the film, and definitely not on the news, but it’s the hottest term on the search engines.

Train to Busan’s plague is, all three, the culmination of capitalism, its implosion, and a kind of cleansing fire. With the collapse of capitalist society, what is left of Seok-woo? Being a hot-shot hedge fund manager doesn’t count for shit in a world where even the trains don’t run. All he really is now, is the parent of a scared little girl, a ten-year-old who blames herself for dragging her father into danger by insisting on a train ride to Busan. His only obligations now are human ones, to his daughter, and to the wife of the man who saved his and his daughter’s life.

“Sir, this started at YS Biotech. The centerpiece of our plan! Sir! All of this has… nothing to do with us… right? We only did what we were told. Is this my fault?”

“It’s… It’s not your fault.”

The blood is on Seok-woo’s hands and it’s a spot that won’t come out.

There are gentle touches throughout the film that allow the viewer to more deeply appreciate the humanity of its characters, all well cast. Train to Busan is Yeon’s first live-action feature, and it looks like his experience in crafting sharply silhouetted animated casts has translated to this film.

“A cluster of troops attacked each student [protester] individually. They would crack his head, stomp his back, and kick him in the face. When the soldiers were done, he looked like a pile of clothes in meat sauce.”

—From Lee Jae-eui’s memoir, Kwangju Diary: Beyond Death, Beyond the Darkness of the Age

Sang-hwa (Ma Dong-seok), the working class strongman in the film, strides in a flashy navy blue blazer and blue denim jeans because they couldn't tattoo “BLUE-COLLAR” onto his forehead. His pregnant wife Sang-hwa (Jung Yu-mi), wearing the cutest embroidered maternity smock Tolly and I have ever seen, is clearly doted on and well-cared for by her tough husband. Su-an clutches a yellow polka dot backpack tenderly and never touches the Nintendo 3DS XL that her dad bought just for the train ride (it’s still in the box!). Yong-guk (Choi Woo-shik), an awkward but earnest young athlete, is visually linked to the rest of his teammates, a sort of surrogate family, all clad in the same baseball jacket as him and wielding baseball bats, making his tragic separation from them all the more jarring. And you can quickly eye which of the two old women parented and spoiled which; these two sisters adapted to, survived, and carved themselves a place in both the junta and post-junta South Korea in radically divergent ways.

Genuine sympathy for beleaguered humanity is rare in apocalyptic films and disaster thrillers as a whole, which tend to treat the masses as nothing but lemmings. These blockbusters, everything from Volcano about people burning to death in LA, to The Day After Tomorrow, about people freezing to death in NYC, almost always stand solely on spectacle and on the novelty of “Oh my gosh! What if” scenarios, falling back onto simplistic misanthropy. Train to Busan definitely has a lot of the former (“What if we put fast-moving zombies on a train? And what if we just punched zombies with our bare fists?”), and an unfortunate bit of the latter.

But add a ringing condemnation of the rot of the current capitalist order—and that’s why people, bound in their homes and fearing for both their lives and their livelihoods—even more so than usual—are streaming Train to Busan en masse.